Grundgestalten are such gestalten as possibly occur repeatedly within a whole piece and to which derived gestalten can be traced back. (Formerly, this was called the motive; but that is a very superficial designation, for gestalten and grundgestalten are usually composed of several motive forms; but the motive is at any one time the smallest part).

Schönberg. June 11, 1934.

1. Let’s call it a game. Brahms leaves traces that make it possible to identify connections among thematic formations of a composition. It is a game of analysis and it exposes one of the most characteristics pleasures of this human activity — a curious interplay between what is presented as direct experience and subjacent levels of signification and reference. The whole process points to the realms of another game, composition itself, imagined from the traces left by the compositional process, insofar as analysis is able to recreate them. Both processes involve interpretive activity.

2. We shall follow the path established by Schönberg in this 1934 fragment: the study of the processes involved in the derivation of gestalten in a piece, and also the integration of motive forms into these composed wholes, taking J. Brahms Sextet op. 18 in B flat as reference and departing point.

Accurate description and understanding of these processes will make it possible to pose other questions concerning motivic work, taking it as a significant process not only in relation to the study of structures but also in the broader perspective of musical meaning formation. Brahms music is particularly suitable for these concerns, and it has always puzzled its best interpreters as a fascinating but also disconcerting blend of emotional impact and strict compositional planning.

Ex. 1

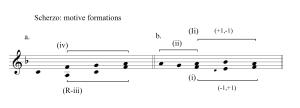

3. The first gesture of the piece — the neighbor-note figure of mm. 1-2 — is already a complex integration of four motive forms:

Ex. 1a

Our analysis will show that these four motive forms remain significant throughout the piece, and that they will be involved in several thematic constructions, leading to transformations and generating new materials.

It should be noted that motive forms (i) and (ii) are neighbor-note figures, (iii) is an arpeggio and (iv) a passing-note figure. There is no real voice projecting this last motive form, it is a kind of voice leading effect, but rather audible and effective as a compositional material – the so called transition theme, on A, will project it (a – b- c# – e…), m. 61, and we will discuss this in detail later.

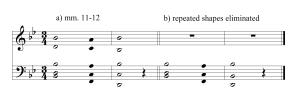

The repetition of the initial phrase (m. 11), now with a full texture, gives us an opportunity to reevaluate the analysis. The results are quite similar, although motive form (ii) is absent and motive form (iv) is represented by its retrograde form (R-iv: d – c – b flat).

Ex. 2

4. But what is really interesting and thought provoking in this initial gesture is the fact that it points to the construction of something which transcends the motive forms. This reinforces Schönberg’s statement that a Grundgestalt is composed of several motive forms.

The following example presents a composed motivic formation that certainly deserves such denomination and that also projects a traditional counterpoint figure — the ‘horn fifths’.

Our analysis will show how this complex formation, the Grundgestalt, is present in several distinct contexts offered by the piece.

Ex. 3

5. Examples 4 and 4a present the same motivic configuration in a minor context (d minor), the beginning of the second movement, the celebrated Andante. It should be noted that the neighbor-note motive (i) has been displaced to the bass (d – c# – d). Ex. 4a shows how motive (ii) is elaborated in the soprano voice (f – e – f), as part of the larger motive iv, now in a minor context (d – e – f). The horn fifths is presented here in its ascending form (sixth, fifth, third).

Ex. 4

Ex. 4a

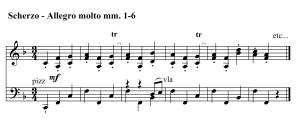

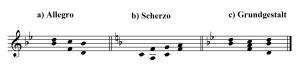

6. This same ascending form appears in the next examples (the beginning of the Scherzo), composed by motive forms (iv) and (R-iii) – superior and inferior voices. The note of the Dominant (c) has been included as part of the melodic game, expanding the initial melodic space to a sixth (c – a), an important analytic detail to be commented later.

But what should be said in relation to the neighbor-note motive forms, are they absent from the beginning of the Scherzo? No they are not. Pay attention to the important melodic relationship (a – b flat) mm. 3-4, transforming the contour of motive form (i) from (-1,+1) to (+1,-1), an inversion (Ii). Ex. 5b shows the complementarity between motive form (i) now appearing in F (f – e – f) and its inversion, and also the presence of motive form (ii) as emphasized by the trill, m. 2.

Ex. 5

Ex. 5a

Ex. 5b

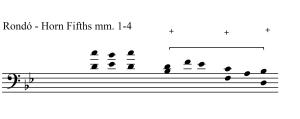

7. The theme of the last movement, the Rondo, displays the same elements. Its first gesture projects the neighbor-note motive form (i: bflat- a – bflat), combined with its inversion transposed a third up (Ii: d – eflat- d), in fact, resembling (ii). After that, the horn fifths is presented in a deliciously disguised form, the fifth appears only in the last eigth-note of the third measure.

Ex. 6

Ex. 6a

8. But did Brahms really think about all these hidden similarities? This is a kind of inevitable question posed to analysts as they expose their ideas about how the music works in terms of subjacent relationships. “No, it’s a coincidence…”, says the annoyed analyst.

Well, after demonstrating the presence of the same figure in the themes of all the four movements, the discussion about intentionality needs to be rephrased. The real question seems to be the tension between hiding and revealing, a significant part of the musical experience proposed by Brahms. And, therefore, the need to include motivic analysis as an important interpretive tool.